Recently, I have been getting questions about possible bird damage in early-heading rice fields. Blackbirds, primarily red-winged blackbirds, can damage rice from planting season, seedling stage, and the ripening period; however, in California, where the majority of our rice is water-seeded, typically damage is limited to the ripening stage. Blackbirds harm the rice crop by “pinching” the rice kernels (squeezing a grain with the beak to force the milky contents into the mouth) at the milk sage, hulling grains and consuming them in the grain stage, and breaking panicles by perching and feeding throughout the ripening period.

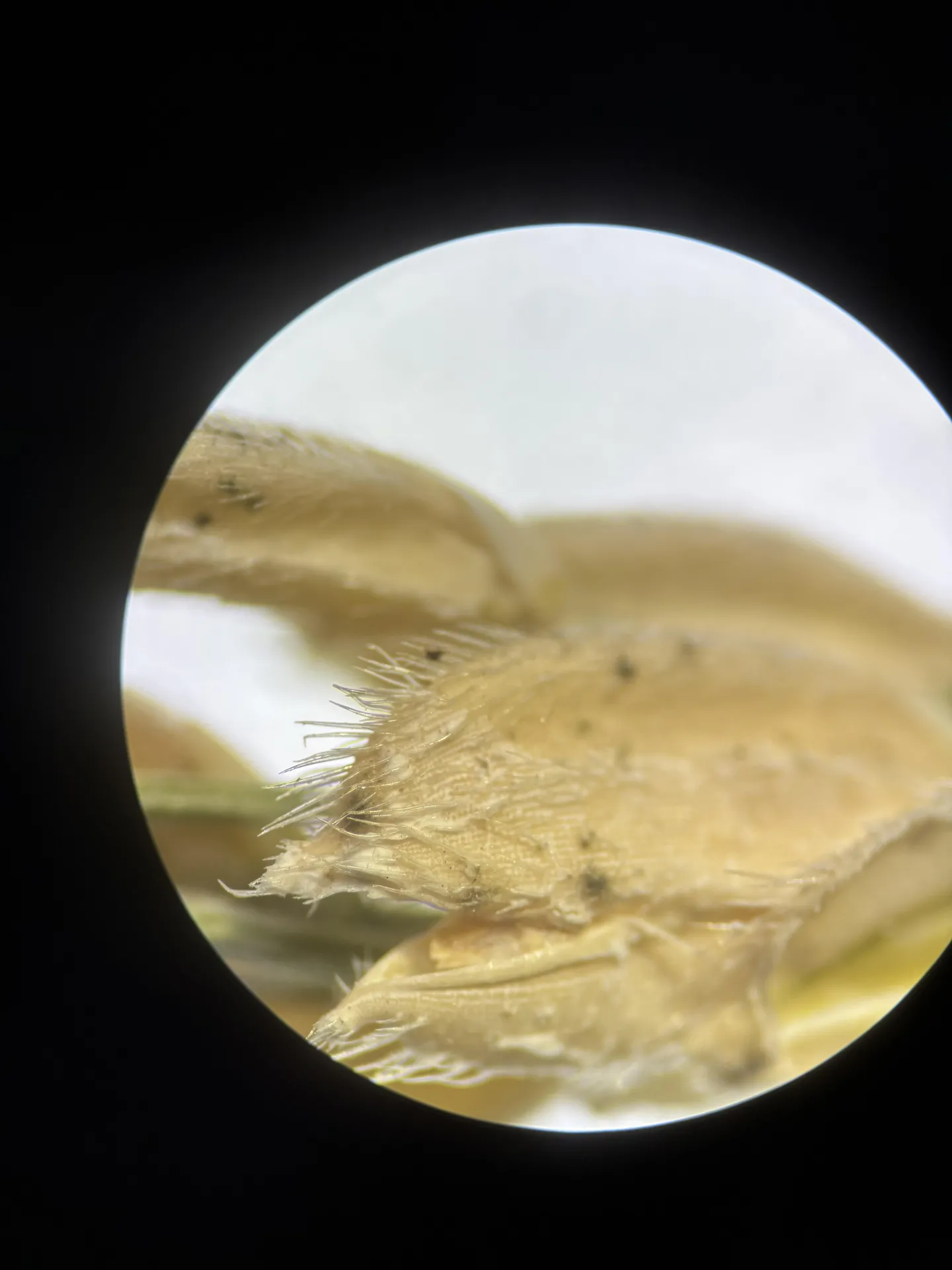

Top: Bird feeding damage in Akita rice. Bottom: Close-up of "pinching" damage from blackbirds.

It is difficult to estimate the economic losses from blackbirds in rice fields. Across the entire United States, overall blackbird damage to rice crops has been estimated to >$20 million, which does not encompass the funds spent on damage abatement efforts. Losses can be high in some fields that are close to important or historic roosting areas. Fields that border roosting habitat (sloughs, tules, bamboo stands, willows, etc.) may be subject to increased depredation.

Early-heading rice fields, especially those that are surrounded by later-heading fields, may be more susceptible to high levels of blackbird infestations, as the birds will all congregate at the available food source, instead of disseminating throughout the region.

As far as management of these blackbirds goes, the most common method is to use frightening/hazing techniques; however, these techniques offer mixed results at best. These include propane guns (zone guns), Mylar tape, and other sound and visual scare devices – in some regions, drones are used to attempt to frighten pest birds; in others, laser scarecrows have been used to attempt to reduce damage – but the birds can habituate to these disturbances so they may only have short-term effectiveness. To be effective, hazing techniques must be implemented as soon as birds appear in the field.

One option used as a bird deterrent: inflatable tube man.

Blackbirds have some protections under the Migratory Bird Treaty Act; however, through a Federal Depredation Order (50 CFR 21.43) issued by the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service (FWS), people are authorized to lethally take some blackbird species, when they are involved in certain damage situations, without a Federal permit. The red-winged blackbird is covered by this order, but the tricolored blackbird (see pictures below) is not covered and cannot be taken under this order.

Left: Male tricolored blackbird. Distinctive red shoulder patch bordered below by a white band. Photo by Daniel Murphy, Macaulay Library.

Right: Male red-winged blackbird. Shorter bill; these birds have a yellow stripe below the reddish-orange patch. Photo by David Trescak, Macaulay Library.

Left: Female tricolored blackbird. Thicker bodied bird with a slender, pointed bill; dark grey-brown overall with streaks on the back and belly; note pale eyebrow. Photo by Paul Fenwick, Macaulay Library.

Right: Female red-winged blackbird. Stocky, broad-shouldered bird with a conical bill; yellowish wash around the face. Female birds in CA often have more cinnamon tones to their feathers. Photo by Brian Sullivan, Macaulay Library.

Nonlethal methods to reduce damage by protected blackbirds must be tried each year before using lethal controls and state laws should also be checked before acting. For bird species not listed in the Depredation Order, a Migratory Bird Depredation Permit must be obtained from the FWS, and State laws must be consulted and adhered to, prior to initiating actions to remove birds or handle their nests and eggs.